Welcome to the New World.

2011 is turning out to be the year of the role-playing game. The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings, Bethesda's Skyrim, the next installment in the Elder Scrolls series that has, amazingly, been going since 1994, Dragon Age 2, Fable 3 (PC edition), Deus Ex: Human Revolution, and, until it was pushed to 2012, Mass Effect 3, all were due for release this year. They are all RPGs, and, all slated to sell extremely well.

Together, they represent somewhat of a renaissance of the genre: on release in 2007-8, the first Witcher was the only PC roleplaying game with high production values and an engaging story, that seemed to be happy to be an RPG. Bioware's Mass Effect, not released until 2008 on PC, was much more concerned with becoming a game about shooting and talking, with all other aspects becoming slowly extraneous, in spite of a fair number of RPG tropes still remaining.

Yet it was also divisive. Leaving aside the issues of the dodgy translation into English from the Polish, the game set the player's role at the start. Instead of the ability to choose who you wanted to be within its world, The Witcher gave you the role of Geralt, the titular character, and that was that. It is facinating that The Witcher 2 is the game being held up by many fans of so-called 'traditional' RPGs as the only game in the list which would fulfill their expectations.

All of the games listed above are, to an extent, part of the 'action RPG' genre. The skill-set involved in playing them may be influenced by the statistics of your character, but it also involves timing, more kinetic action, first-person or over-the-shoulder third person cameras, and a high degree of player reaction required in combat.

This is not new for the RPG, but it does make a marked change to ten years ago, and signifies the final closure to the predominance of Dungeons and Dragons's long-lasting influence over the genre. It had been slowly ebbing away for a while, with perhaps Dragon Age: Origins its final death throes, but the fact is that the RPG that we have now is a vibrantly different beast to the genre's origins. When Kieron Gillen commented back in 2006 of Neverwinter Nights 2 that "there's a nagging sense that - perhaps - we're reaching the end of the road of the Black-Isle/Bioware model western-style role-playing game" he was talking about the particular model of RPG, the top-down, isometric, heavily stats-based style that reached its apogee with Baldur's Gate 2.

Let's look back, briefly.

Dungeons & Dragons, for those who have never encountered it before, is in many ways the original fantasy roleplaying game. Designed by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, and first published in 1974, it plays like a board game, but where the players choose a role from several set fantasy races, and proceed to roll dice to determine their character's skills. One player dictates the story and controls everything outside of the other players' actions so that the players' interactions are not merely with a rulebook. The players act as adventurers questing into dungeons that, in many ways, are modelled on Tolkien's Mines of Moria, or the caves under the Misty Mountains. Playing on a paper board, it allows players to design their own maps. The group of players may have a mission to complete, to defeat the evil goblin king, or to gain as much gold as possible. On their way, they encounter enemies, traps, and other problems for them to deal with: the 'Dungeon Master' player being the person who decides what these may be (although he may be following a pre-written script). The traditional D&D stories are simple, and the world around it is American Tolkien-inspired generic fantasy.

The crucial aspect of D&D for videogames is how conflicts were resolved. Through dice. Using the statistics established at the start of the game, dice would be rolled to determine whether players had succeeded or failed in overcoming their challenges. Dice rolls + statistics are easily simulatable by computer, as is the limited map on which D&D was played. By positioning the computer as the 'Dungeon Master', computer games could offer the D&D style of gameplay, solo. Furthermore, they could introduce the idea of this sort of gameplay to people who would never dream of touching real-life Dungeons & Dragons with a bargepole, due to the game being positioned somewhat on the extreme end of the geek spectrum.

However, with its set structure, of a part of adventurers, detailed statistics, multiple stock fantasy races, and random-number-based combat and challenges, D&D became the prime basis for computer role-playing games for the best part of two decades, 1985-2005.

This, to me, is a great shame. Part of the problem with American fantasy is that it is only able to take the trappings of Tolkien - the proto-medieval world with a mythic past; the elves and dwarves; the noble heroes; without engaging with the aspect of Tolkien that is so remarkable - the worlds created in American fantasy never feel truly old, nor do they feel lived in. They exist to support the game, and the roll of the dice, and do not rise much beyond the twee. Whilst Richard Garriott's Ultima series, particularly Ultima 7, has much about it that is revolutionary in terms of the level of interactivity with the world, Garriott cannot resist narcissistically placing himself inside the narrative as the ridiculously-named 'Lord British'. The characters 'thee' and 'thou' throughout, in a manner that never fails to grate. The worlds created are superficial, as are those of much generic fantasy fiction, and they fail to engage. Since D&D-inspired games ae viewed top-down, as with a boardgame, they are not worlds you could live in - they are games you are playing. The random-number-generation which fills every aspect of the games only pulls at the immersion even more.

Interlude: Board games. Board games are great. But for me personally - as with the rest of this article, these merely represent my own views - the joy of board games is in the social experience of playing them with a group of friends or family. The interaction between you and the other people involved is key. The way they suck me in is by providing mechanics that enable the social dynamic to work, or be challenged. This is not the same with computer games of this type - the social dynamic is with NPCs, which at once makes them vastly limited in comparison, but also part of the story. The issue then becomes, for me, how I want that story to be told to me, and how I want to take part in it. Board game mechanics where you are, essentially, playing solitaire with the computer don't appeal to me in an RPG, as the process doesn't engage: the view is too limited, the mechanics too obviously those of a game. I want to be lied to in a role-playing game, to pretend that the world presented could be one in which I could exist. This doesn't work for me when they follow the look and mechanics of board games.

However, parallel to this development strand, of the D&D-based game, was the immersive sim. The idea behind these games was more complex, more focused on the individual player. Looking Glass Studio's Ultima Underworld began this trend in 1992, and it was followed by the first Elder Scrolls game, Arena, a year later. The idea behind the immersive sim was to create a world that would be as interactive as possible for the player, who would view the world from the first-person. The narrative would be led by how they interacted with the world in their own way, but the game, while containing player-generated statistics, would rely much more upon action-game elements such as timing, and three-dimensional interactivity, so that the necessary skillset for problem-solving and combat was not a purely tactical one but also a reactionary one. Here were worlds you could live in.

During the 1990s, however, computer game design was not focused on the immersive sim: the generation of developers who had grown up with D&D were still active and leading the field, and that fact, combined with the enormous effort involved in generating the technological framework for an immersive sim, made them all too rare. 1994's System Shock and 1996's Elder Scrolls: Daggerfall were virtually the sole mid-90s games of this ilk. In fact, Looking Glass Studios (which partly became Ion Storm Austin in 2000) and Bethesda was virtually the only major developers making games of this style throughout the 1990s, and both had a slow rate of releases for this type of title. It was this subgenre of game, however, that was to merge with the traditional RPG, and third-person action games, to form the modern RPG we have today.

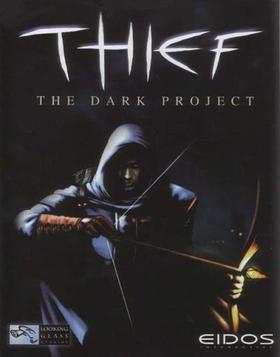

Taking the first-person perspective of a shooter, with the post-Quake free aim mouselook, Thief: The Dark Project, System Shock 2, and most notably Deus Ex (1998, 1999, 2000) merged role-playing elements with locations in which the player could roam freely, interacting with a growing variety of aspects of the world. Games of this type require a great deal of effort on the part of the developer, and it is perhaps no surprise that they remain relatively rare. Their worlds are detailed enough that there is a sense that the world could continue without the game plot taking place at all, something not so true of the games inspired by D&D. There are exceptions, games which walk the borders between the immersive sim and first-person shooters, like Bioshock, but even games like STALKER, set in a Roadside Picnic/Tarkovsky-inspired radioactive 'zone' around Chernobyl, set up an active world that exists without player action causing it to behave the way it does.

The immersive sim at its peak, by letting you see through your character's eyes, with an interactive and tactile world, can create a remarkable sense of place. Deus Ex and Vampire The Masquerade: Bloodlines in particular excel at this, at least in parts. Visiting the US a few years ago, my first thoughts on seeing Battery Park in New York, and Santa Monica Beach in Los Angeles, was that I had been there before. And I had. Playing Fallout 3, walking through the ruined Washington D.C. National Mall, I was eerily reminded of the genuine article.

Of all the RPGs being released this year, two are unashamed immersive sims: Skyrim, Bethesda's latest Elder Scrolls game, and Deus Ex: Human Revolution, the second sequel to perhaps the greatest immersive sim of them all. Whilst it is something of a shame that the sole two games of this ilk are sequels, and so unlikely to push the subgenre in new directions, it is perhaps a sign of how little the immersive sim has evolved that the games that first progenated these series were published in 1994 and 2000.

The third crucial influence over The Witcher 2, Mass Effect 3, and Dragon Age 2, is the third-person action game. After an uneasy start with Fade to Black, Tomb Raider popularised the form in 1996. The global success of Grand Theft Auto III in 2001, with an open world all viewed from behind the protagonist's head, established it as a predominant style for action-oriented games in which the player-character was a narrative figure as well as a cipher for the player, and Max Payne, followed by the enormous success of Gears of War made it a successful format for shooters. Bioware, one of the key developers of the traditional RPG moved to a third-person focus with their games from Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic in 2003, and their releases, alongside the three GTA games released following III, demonstrate that third-person has become the prime method of telling lengthy, detailed narratives in games. Indeed, the recent LA Noire is the current culmination of storytelling in this form.

Why is third person important? The view. It allows you to stare into the distance, following the eyeline of your character, rather than it being limited by the edge of the screen in a top-down game. You face forwards. At the same time, it positions the character on the screen, in front of you, at all times. Here is your role, you are playing as this person right here. This person, unlike in a first-person game, is explicitly not you, but by being able to follow the eye-line of the character you are playing, you see what they see. This places you in the world, but keeps the character you are playing firmly foregrounded.

Merging these elements with the old-school RPG has meant a great deal of whisking of ideas, of formats, and of styles. There has been a steady move away from statistic-led challenges and turn-based combat, which remained in Bioware's earlier third-person games. The action in The Witcher 2 is not statistics-focused as much as it is a question of timing, and there is but one character that the player can choose. The Mass Effect games present a new model, a game focused entirely on shooting and conversation, ignoring the traditional tropes of RPGs entirely, but framing the action gameplay with a complex and intricate story, that can play out in many different ways based on player action and choice.

Dive in.

I think you're making the "The only true immersion is trying to be the holodeck!" fallacy. There's nothing about rolling dice or top-down perspectives per se that limit immersion; Board games manage it fine, after all. I'm not sure you've ever played D&D - If not, you probably should try it before denouncing it as a crippling influence on games.

ReplyDeleteBesides that, if viewing things from a top-down perspective is anti-immersion, why is third-person different? You've got a paragraph mentioning games that do it, yes, but you don't say why.

I agree with Jack. Its a fine article, but I just disagree with it. I found Baldur's Gate 2 very immersive- I felt a sense of place and scale in the world, and that was due to good game design. Indeed, FF7 is pretty immersive, and certainly creates a sense of place.

ReplyDeleteWhat I would argue is that being attached to D20 mechanics is silly. While having turn based games introduces lots of options, theres no reason to have a system restricted necessarily by humans having to do all the statistics. When you have a big ol' computer to do all the mathematics then you can have a much more in depth system without actually sacrificing anything from the player's point of view (for instance, individual hit locations might be an utter pain in offline gaming, but just as easy on online gaming)

The problem when real-time action is introduced is that it really ceases to be an RPG, because you are no longer simulating the skills of your character; it's the player's skills that are being tested. I have nothing against story-based action games, but that's what they are -- story-based action games. Not RPGs, despite the trappings of levels and skills. Are they dying because kids no longer play tabletop RPGs like D&D, and don't understand the distinction between character and player? Probably.

ReplyDeleteIn real life, when you try to hit someone with a sword, you body doesn't do a canned animation that is the same every time and that is guaranteed to puncture the skin of anyone a meter in front of you.

ReplyDeleteIn real life, attempting to hurt someone with a sword is a mixture of skill and luck, something much more like a dice roll than the kind of thing that happens in an action-RPG.

And I agree with Jack Shandy that it's kind of pathetic that you think the only possible kind of immersion is pressing the player's nose up against the game world and trying to make him think, "You Are There!" Have you never read a book?

I think Mr K and Jonathan make good points - to a degree. Mr K's point about dice rolls I entirely agree with (and forms much of my criticism against D&D mechanics). Jonathan's point regarding it no longer being about simulating the character but instead being about player skill - I think this is true, up to a point, but you can certainly make a case that Deus Ex and Morrowind/Oblivion manage to find a decent balance between player skill and character abilities through the statistics/aim deficiencies present before levelling up.

ReplyDeleteJack also makes a good point - I hadn't mentioned why third person perspectives were more immersive than top-down, although I obviously would argue that they are. My answer would be that it gives you a much greater sense of focus, and gives you a perspective that is enough from your character's point of view while keeping you fixed on the avatar you are playing as, which does go some way to establishing that you're playing as a character rather than yourself in the game.

I think it depends what people get their kicks from. I love - and work in producing - books (and have played D&D, although not since I was a whole lot younger) and they are immersive as stories. That's great. Computer games, from a personal point of view, I want to be immersive as interactive experiences. I find that much more engaging than a simulated boardgame, or choose-your-own-adventure, for me. I actually happen to think that the holodeck fallacy is rather belaboring a point that is rather unnecessary - that there are different types of games that people can be engaged with. I have no problem with that, but that doesn't change the type of experience I want from - or are suggested by - the RPGs I personally enjoy playing.

Finally, Michael, I think you're barking up the wrong tree. The sword point is a failure of game engines and bad mechanics, not of the form. In real life, when you hit someone with a sword, you quite often will try and use a set of moves that you know works. These can be repetitive (although you will mix them up, obviously). The skill is in how well you execute them, and in timing. Luck doesn't come into it all that much. The best action games know this and let your hits be a combination of character skill and timing. This seems to me a much better simulation of real life than dice. Cf. The Witcher 2.

Also, I never said the 'only possible' kind of immersion is first-person, but that's beside the point.

In real life, when you hit someone with a sword, you quite often will try and use a set of moves that you know works. These can be repetitive (although you will mix them up, obviously). The skill is in how well you execute them, and in timing. Luck doesn't come into it all that much.

ReplyDeleteThis describes a fencing match, not a battlefield or a raid or any of the other typical RPG battle scenarios.

This describes a fencing match, not a battlefield or a raid or any of the other typical RPG battle scenarios.

ReplyDeleteYes, because in a typical RPG battle scenario you aren't playing as an untrained, panicking person - you're usually playing as a trained warrior. Training in sword-fighting, even heavy, two-handed swords, involves repetitively learning moves and being able to replicate those in the appropriate situation. If your character is skilled in that, then that is what they would aim to do. That makes it entirely acceptable that it becomes about skill and timing. Of course I'd love a greater degree of choice over what moves to chose and variationss in animation, but I think the point stands.

Not quite sure about this piece.

ReplyDelete"Since D&D-inspired games ae viewed top-down, as with a boardgame, they are not worlds you could live in - they are games you are playing."

An entire generation of Ultima fans would thoroughly and happily disagree with you, as would the people who still maintain that the earlier, top-down Japanese RPGs are superior to the newer over-the-shoulder ones. There is no reason whatsoever to think that world-engagement is a function of POV. That anybody could think otherwise just strikes me as a function of a profoundly limited perspective.

That paragraph on Tomb Raider et al also mistakes popularity for effectiveness. Yes, the third-person exploration/combat game became very popular at the time. Why wouldn't it? It was novel, and served to showcase ever-increasing graphic capabilities quite well. But to argue that that popularity was due to its ability to create greater intellectual and emotional engagement ("immersion" is kind of a terrible word for that) is very, very questionable. Questionable at best. Now that graphics have levelled out a bit, and the novelty of over-the-shoulder is gone, there is probably room for other perspectives that are equally engaging.

(Certainly Starcraft players seem to be fond of isometric.)

Finally, I completely agree with Jonathan Badger. RPGs, at their core, are about engagement with not only a fictional world, but a fictional character; it's about an avatar with different abilities and skills than the player's. That isn't something that need be "balanced" with tests of player dexterity, as was implied in the comments about Oblivion/Deus Ex. Why test player dexterity when the point is character dexterity? Would you test player strength the same way?

There are already more than enough games that serve as little more than tests of a player's ability to put crosshairs on a man's head and push a button. That's not "immersive". Let's not relegate RPGs to that same dismal fate as everything else.

And just one other thing: I think we can all agree that what defines an RPG is neither "fantastic setting" nor "character plot arc". You can have an FPS in a fantastic setting, and you can have oodles of character plot arcs in a good ol' manshoot. Duke Nukem Forever wouldn't become an RPG if Duke got dialogue trees.

ReplyDelete