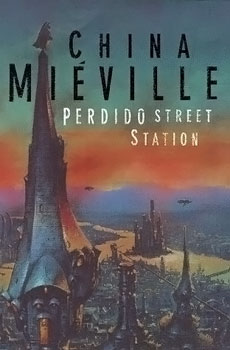

Steampunk gothic horror; the screaming clank of dark iron machinery; birds who are men; cacti who are men; beetles who are men; men who have been remade into creatures of horror. Welcome to Perdido Street Station. How will you sleep at night?

Perdido Street Station, the second novel by genre sensation China Miéville, and the first of his books set in the grimy depths of New Crobuzon, is a shatteringly bleak, dark, and flashily original work of the fantastic, first published in 2000.

|

| China Miéville |

The book follows the science-fiction/fantasy genre custom of being large enough to, in Neil Gaiman's memorable phrase, stun a burglar, but it has the advantage of being a self-contained narrative, and the story arc, while not wholly satisfying, is always engaging. It is a novel that can be read fast, with great intensity, soaking up great swathes of imagination that ripple through it, recoiling with disgust in parts, and revelling in the pacey, unpredictable story.

The focus of the novel is Isaac Dan der Grimnebulin, an inventor and former university researcher, and his insectoid lover, Lin. Each is commissioned to create the impossible by separate, demanding clients: Isaac to restore the gift of flight to the bird-man Yagharek, whose wings were cruelly hacked from him as punishment for an untranslatable crime; Lin to create a statue of the Remade crime lord Mr Motley. As part of his investigations, Isaac receives a caterpillar-like creature which he discovers eats a hallucinogenic drug colloquially known as 'dreamshit'. All three situations strip the characters from what they know, shoving them brutally into vicious, unrestrained narratives that tear them apart.

There are very few sympathetic characters in this book besides the leads, and this is a book that creates a constant sense of Lovecraftian unease. Something quite horrible will, you feel, happen to any of the characters at any moment throughout the book, and often does.

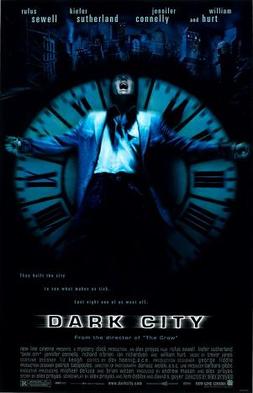

Yet despite moments of pure horror, Miéville isn't interested in purely playing for shock. His imagination is whirring too much for that. Like Alex Proyas's Dark City, Miéville's world is bleak, dark, corrupt, and smog-ridden, but it is well-constructed and rich enough to not fall down under the weight of its own steam-punk gothic imagery, and it feels lived in. It is a world that sweats, that pustulates, and Miéville luxuriates in its grime.

Oddly enough, the reference point that I kept being reminded of was my partially-forgotten memories of the fiction behind Warhammer 40,000, Games Workshop's tabletop wargame into which several generations of middle-class British kids have been inducted into around the age of 10. Set in a grim, mechanistic future where humanity has reached for the stars and found only war, the bleak backstory of Games Workshop's game, and particularly in its spin-off, Necromunda, set amongst rival gangs in the underhive of a vast, steampunk metropolis, feels remarkably similar to Miéville's work, exploring a similar mechanical remaking of human beings into clanking, smoking, squealing machines, their humanity ebbing from them. Part of me would be rather surprised if Miéville hadn't wandered into a Games Workshop at some point in his childhood.

Miéville declared recently that science fiction had become cool, and on winning his unprecedented third Arthur C Clarke award for The City and The City in 2010 he referred to the dismissive comments towards science fiction made by the chair of the committee for the Man Booker prize, yet he is not content with writing science fiction in the traditional manner. His science fiction merges with fantasy, with horror, and with crime (and whilst there is romance, the novel is too bleak to properly complete the 'genre' set). Fantasy as a genre becomes stifling when it cannot escape the shadow of Tolkien-esque medievalism, horror when it is merely interested in shock. Miéville does neither.

The novel is not perfect, and there are some unsatifying lurches in the plot, and some developments of character or narrative that don't sit entirely right, but the book is too alive, it is buzzing too much, for that to be a great fault. Miéville succeeds by making all three genres he has smashed together and remade in a new shape feel relevant and active once more. By making them feel cool. If Miéville is to be proved right, and science fiction's breakout from the genre ghetto is finally upon us, then he will certainly be leading the charge.

No comments:

Post a Comment